backing packing over the Crazy Mountains, 1974, as told by my dad

The year before our youngest child graduated from high school, we were having a good summer. Six refugees from Dixie moved along the ridge as we trudged eastward on our trek from Shields River to the Sweet Grass. We were at 10,000 feet altitude and above timberline. We were also above the cloud line. The sky overhead was blue, but behind us, and below us, a storm was building.

Black clouds caught on the tops of the forested mounds by the Porcupine Range Station. They climbed through the valley behind us rapidly growing in size. Then in a sudden fury, the storm boiled out of the lowlands and crossed the glaciers. Lightning jabbed into the barren ridges. The clouds which engulfed us became fire breathing dragons and chariots for the armies of Mars! Explosions surrounded us and thunder echoed through narrow gorges.

We huddled beside an outcropping cliff huddled together taking courage from one another as cold rain slapped our faces. When the rain ceased, we shivered our way along the crest of the divide. It was dark and misty. Then, for an instant, the fog lifted. From the cliffs below us, valleys branched off like fingers from a hand – Grace Crowell’s blue distances calling like a song.

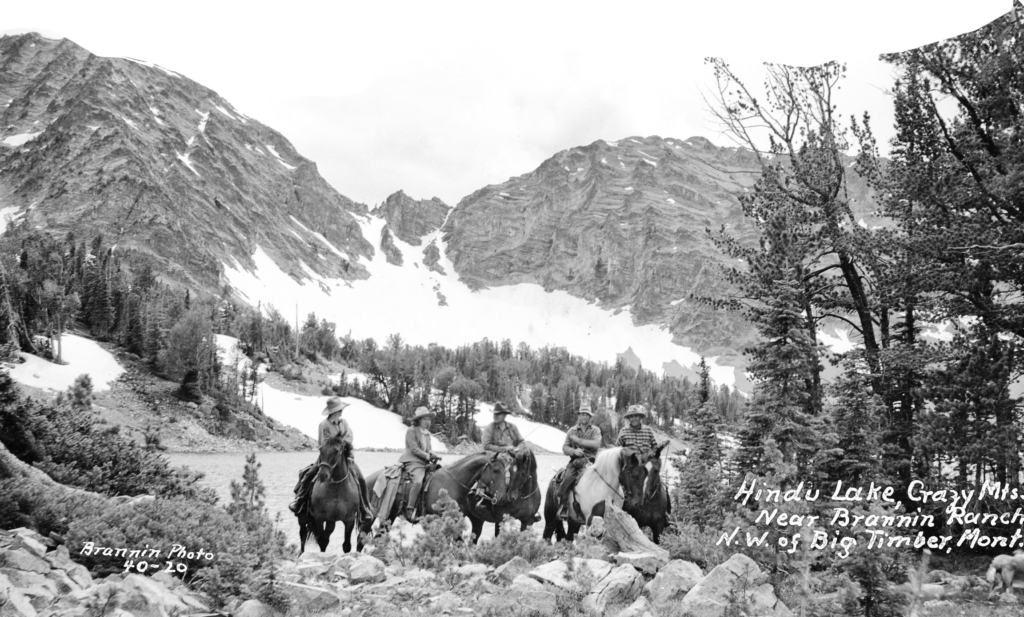

Ten miles away, to the north, a tiny thread of a highway showed us the route to White Sulphur Springs. Behind us, dark clouds still hovered over a quilt top of meadows and farmlands. Southward, a narrow canyon wound into a valley. Then we reached the end of the ridge and looked down into the headwaters of the Sweet Grass drainage. A mountain lake came into view. Campfire Lake, the forest map told us. But I knew it more by another name.

I think this is my favorite new (old) picture!

“Hindu Lake,” Barney Brannin said. “When you get there, just look at the jagged ridge around the lake and you’ll see why. There’s a rock on the ridge that looks like an India Indian with a turban on his head.”

“One time,” he said, “two men from India came up the Yellowstone with a party of Englishmen. These two got put off the boat, or else they left it somewhere between Greycliff and Livingston. They saw the mountains on the north side of the river and headed for the peaks looking for gold. Some say they found it. One of the Hindus returned for supplies but met with foul play before he could get back to the mountains. His companion, the prospector in the Crazy Mountains, is still on the ridges, waiting for his companion to come back.”

We looked above the lake toward the southwest. I caught a glimpse of the Hindu before the mist wiped him out. Then the rain hit us again. We were cold, wet and weary when we arrived at the edge of the water. But there had been a moment that we would remember – a high moment measured by the heart and not by a clock. We had found a place for seeing – a place for finding oneself. William Stidger put it this way:

“Each soul must seek some Sinai

some far flung mountain peak

where he may hear the thunders roll

and timeless voices speak.”

Barney Brannin was right. In this same range Plenty Coups sought wisdom to lead his people. Plenty Coups, Chief of the Crows, could have said it with us. “Mountains are for visions.”