a real tale by my grandfather, Bee Knapp

The Missouri is a slow river and the ice freezes real deep. My cousin liked to load a sleigh full of folks and go to the UL ranch for a couple of days to dance. He had his horses sharp ice shod. He liked to drive four horses.

In June the water would come out from Three Forks and the Little Rockies. It would cover the ice. That which got under at rapids and waterfalls made a lot of pressure and the ice would blow. Ice jams would be heard 20-25 miles away.

One of the Missouri River ‘steaders was a little Irishman named Shorty Brannan. One time he got caught by a vicious hailstorm. There was a high wind and hail the size of goose egg. The only shelter he found was a coyote den. Brannan crawled in headfirst as far as he could go. He saved his life, but couldn’t sit down for some time.

Shorty had a homestead on the south side of the river. He had to boat to or swim to it in the summer. In winter he could cross on the ice.

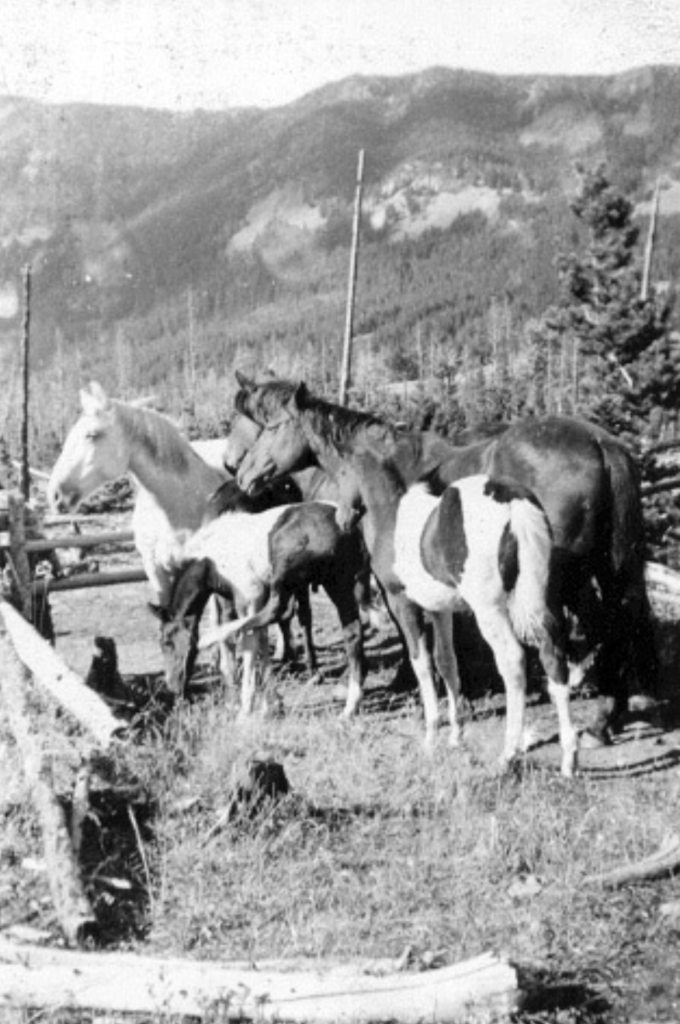

The Missouri didn’t seem to dampen his spirits or interfere with his instinct to be a gentleman. Brannan wasn’t sloppy. He wore a suit, a white canvas suit. He kept it neat. Shorty rode a small, tough horse named Snookums. He kept the horse neat, too.

I was working for one of the Sun Prairie ranchers. That was the bachelor named Gus Tank. He homesteaded north of the river in the Lairb Hills. My father was a fine fiddler. Gus’s mansion was small, only one room, but the neighbors were aching for a party. Two of those pretty, half-breed Reynolds girls came down and said that they were going to have a dance and I was going to be the fiddler. They moved the bed and table outdoors and made a cake. The Sun Prairie people turned out with their jugs, and they danced all night. After breakfast the next morning some of the partiers had to get back to their own homesteads.

One girl, who had a homestead, was a “Blackdutch,” dark haired, single lady. I told her I’d get someone to ride home with her. Then I got Al McNeil aside and told him that Bertha sure needed an escort. The two left on what was the first step toward the hitching post.

Some of the others at the cabin decided they needed to stay around a little longer. They wanted to show off their riding abilities. Bill was a local cowboy who had taken a shine to my sister, Leone. He rode every bronc on the place and was chosen to bust out Gus’ six year old bull.

A couple of hands snubbed the big animal to a post and put a sursingle on him. Bill climbed topside and managed to stay there. The bull sunfished across the meadow but couldn’t get rid of his rider so he headed for the pond. He stopped in the middle of it. Only the bull’s head, hump and rider stuck out of the water. Bill was spurring and waving his hat but to no avail. He had the wettest boots in the country and was hollering for a pickup rider. The bull was in a balk.

Shorty Brannan went to the rescue. He bragged that Snookums could handle any critter on the prairie. Shorty climbed aboard, white canvas suit and all, and urged his horse into the pond. He threw the rope, a perfect shot over the bull’s horns. Brannan dallied a hitch around the saddle horn. When Snookums pulled out the slack, the bull flipped his head sideways and upset the horse. Shorty came dragging out of there, by golly. His suit was in disarray. He washed his clothes down, got on old Snookums. The last we seen of him he was riding over the hill without saying a word.

Bill sort of tarnished his record as a bull rider. He come out wet and muddy. It was just as well. Later on Leone married Charlie Sherod.

A winter or two later, Shorty Brannan was riding Snookums across the river. They fell through a blow hole on the Missouri ice and washed down the stream under the Ice. They didn’t find them until the spring thaw.