by Guest Author, T-Bug

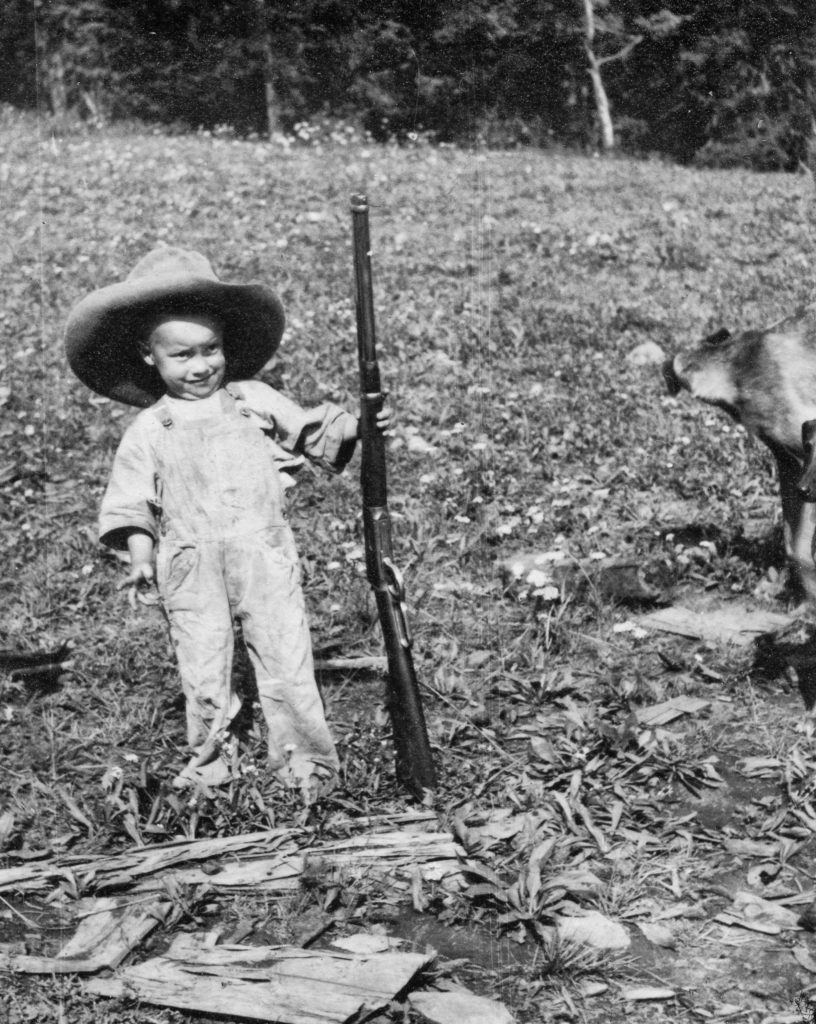

I am not as young as I used to be. That six-week walk-about last year has progressed my downward aging spiral. My rib cage is distended and makes my look twice as wide as before. Arthritis sure doesn’t help matters either. I can barely walk on my bowlegged legs. It would seem that having four legs, at least one of them would work right. My eyes are clouded over, and ears aren’t as sharp as they were at one time. The hair on my legs, feet, and face are getting grayer by the moment. I am sure feeling my age and I might just fall apart at any moment.

Yet, I still have big dreams of being a pup running, sniffing out rodents, and jumping in the air snapping at butterflies. Just last night as I dozed on my little bed, I dreamed I was sleek and slim once again. I whined and yipped and kicked my legs as I chased the wascally wabbit. When the chase was over It took several minutes for me to ease back into sleep. That sweet dream left a smile on my face, and I let out an occasional “ruff.”

My master says I am getting fat and lazy, so he makes me go outside to get some exercise. Yesterday he opened the door and said, “Go on out!” So, since I was outside anyway, I decided to nose around. All of a sudden something caught my dim eyes. I stopped dead still as if coming to attention and strained my stopped-up ears. I saw a quick movement. There it was – one of the few things that still stir my blood – a rabbit! I paused. Did I have another chase left in me? The rabbit saw me and hopped away as he shook his little tail and taunted me. I trotted toward where the rabbit had been. I was about out of breath so slowed my pace and circled the area. It was way too much trouble to chase after that young hare that has eluded me for months. I don’t know what I’d do with it even if I caught it, so I let him go. I was satisfied to find a place to rest. My master finally let me back in and I managed to get up the steps and limp to my bed.

Maybe I will catch that rabbit tonight! Yeah, in my dreams! Arf!