The “Dirty Thirties” blew in more than prairie dust storms, drought, and depression. Those years also blew in death and brought mourning to the Brannin family in Sweet Grass Canyon. You’ve heard it said that deaths come in threes, but those depression years demanded more, claiming five lives from the heart of the Crazy Mountains.

Orval Briner, born in the spring of 1911, was the first-born son of Bessie Brannin Briner. They lived in Indiana though Bessie longed to be with her family in the Crazy Mountains. Every summer, she took the kids back to the Montana ranch. They lived there during the war. Bessie died shortly after, leaving behind three small children and a large family to mourn. The kids were still able to spend some time at the ranch. When the Brannin brothers transformed it into a Dude Ranch, Bill Briner brought the family out to stay and helped build the lodge.

It seemed fitting that “Ollie” was there. After all, he bore the first name of Bessie’s favorite brother, Richard, known as “Uncle Dick.” Ollie learned how to ride horses and bulls. He went hunting and fishing. Surely, he got extra attention from his namesake though none of the slew of kids who found their way to the canyon suffered from lack of love, care, or good-natured ribbing. Many of them spent part of their growing up years there.

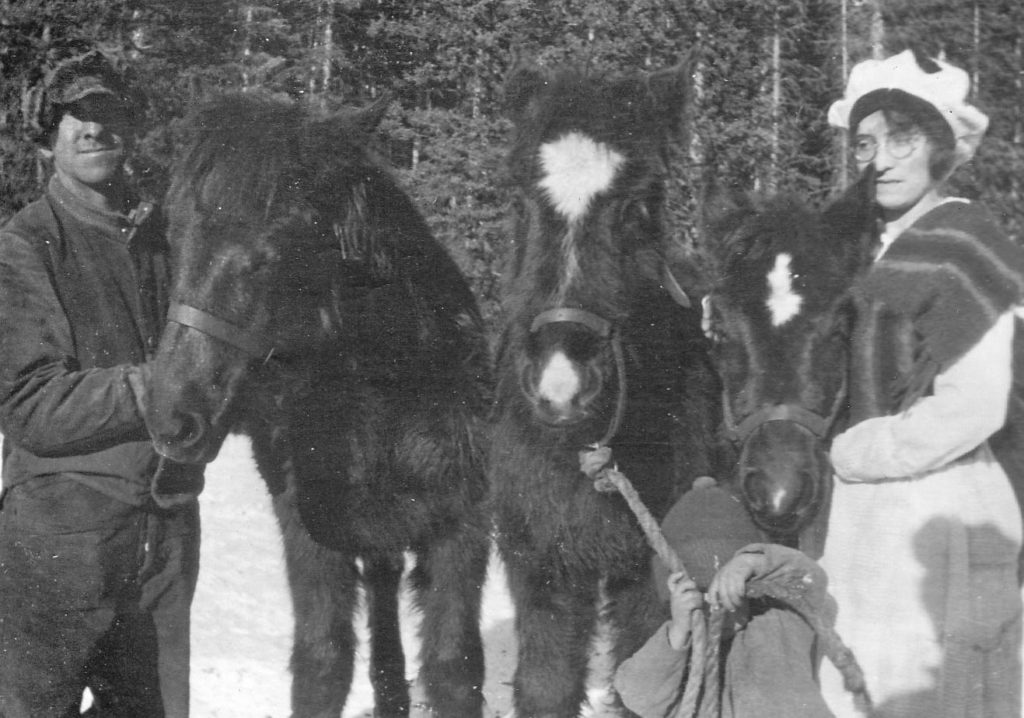

At the age of eighteen, Ollie went to work on the ranch with the uncles. He was also employed by other ranchers in Melville. The 1930 census lists him as a “lodger” in the household of the Tronruds. He broke horses and was trail guide for the dudes. The teacher of the cabin school, Miss Egland, caught his eye, though Ollie did have a bit of competition from a youngster, cousin Buck, who nursed his first teacher crush. Ollie wore a black leather jacket and tamed Leo, the big bay gelding, to impress the teacher. Those years of youth, hard work, fond memories, and puppy love were soon overshadowed by dark clouds of death.

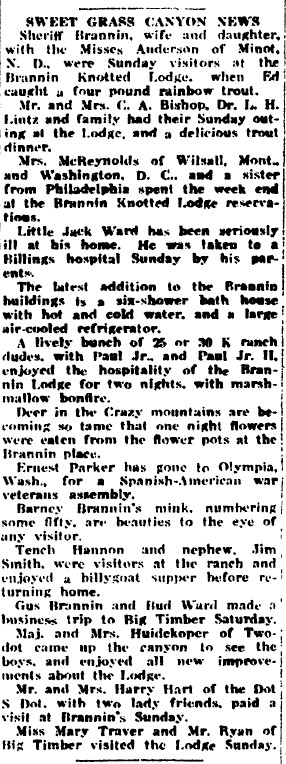

Granny Brannin was the first to go in the spring of 1930. She left behind an overwhelming legacy and generations who continue to retell her story. Maybe it’s fitting that she would soon be joined by others. She thrived in the company of her family, her arms always ready to embrace them in her circle of love. It was only three short months when her oldest son, Dolph, the most affectionate of her boys, joined her. I imagine when they reunited, he swept her across the dance floor. They both loved to dance and since his wife didn’t, mother and son were dance partners.

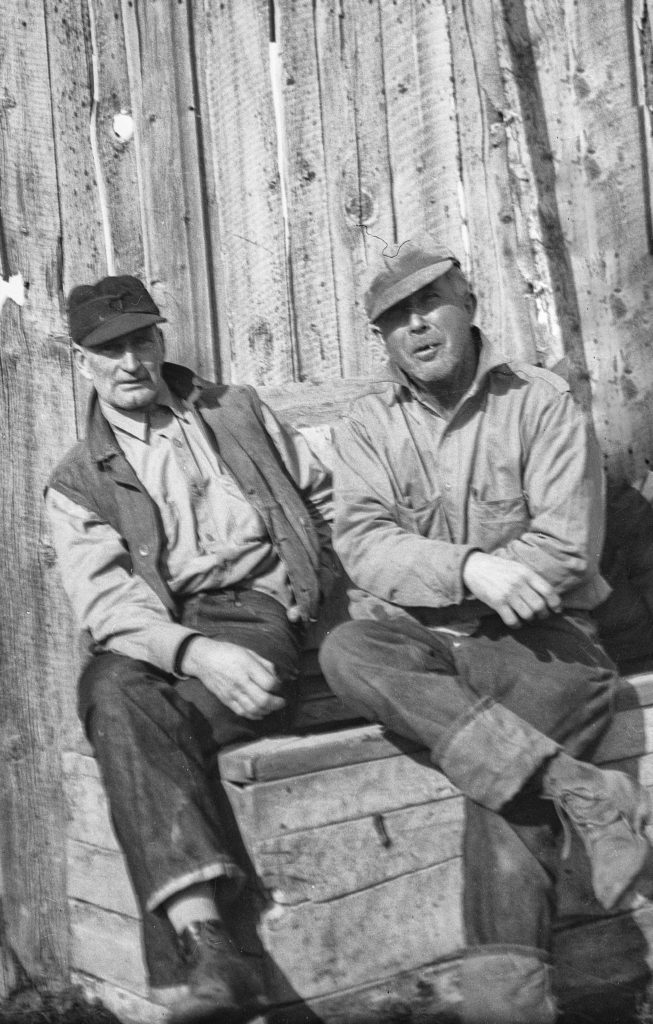

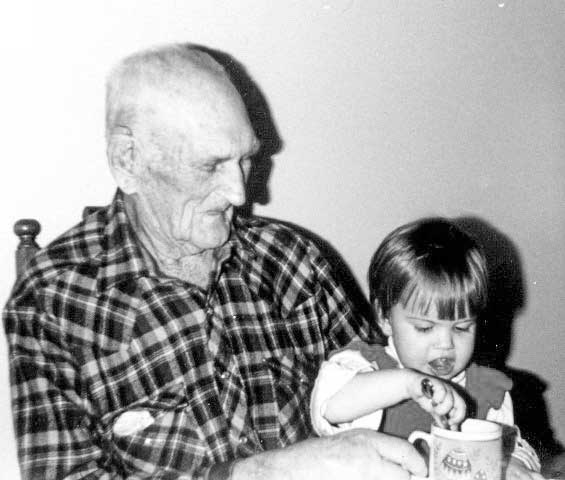

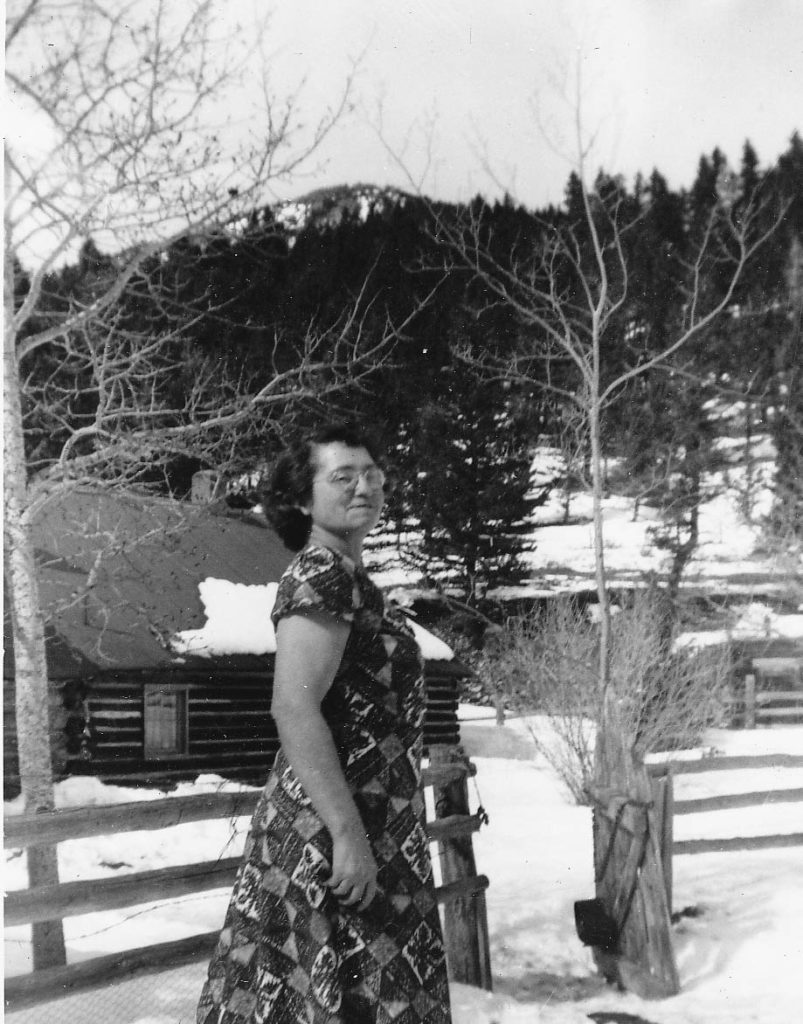

Orval seated left; Jack standing far right

The fall of 1931, fourteen-year-old Jack joined his Grandmother and Uncle Dolph. He had been diagnosed with an inoperable Pontine brain tumor in 1929. It was the egg money given to Jack’s mother that provided funds for their travel to the Mayo Clinic for treatment and prolonged his life longer than expected. Granny Brannin must have greeted him with open arms and introduced him to Uncle Joe and Aunt Bessie.

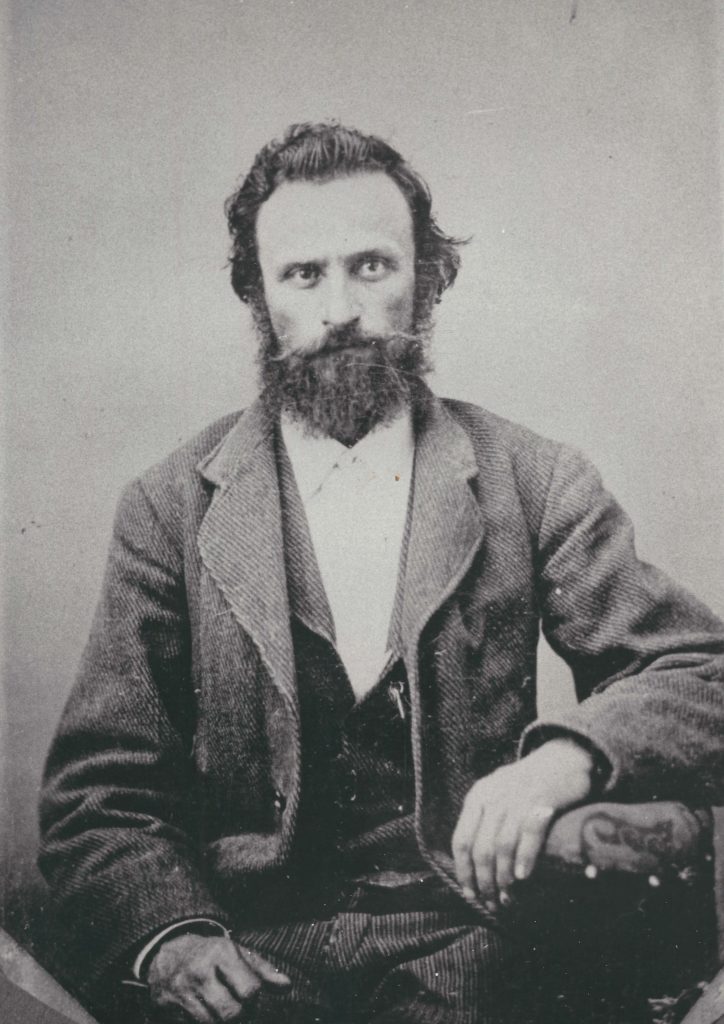

Dolph

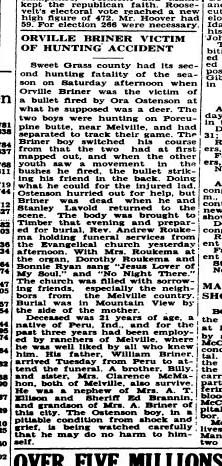

A year later, another was added to the number. Orval, age 21, and a buddy of his, Orie Ortenson, went deer hunting on Porcupine Butte. They split up to track their game. When Orie saw movement in the bushes, he shot, not knowing that Orval had changed direction. Orval was struck in the back. Orie ran for help but when he got back with Stanley Lavold, Orval was already dead. That was November 5, 1932. The newspaper stated, “The Ostenson boy, in a pitiable condition from the shock and grief, is being watched carefully that he may do no harm to himself.”

In 1932, when the whole country wept from depression, there were tears flowing from the heart of the mountains. Grandfather Ward also joined the ranks of death that year. It was a bad year, but Jack’s Mama said that good things happen even in bad years. Sometimes you just have to wait to find the good that comes from such times. Jack’s little brother, Buck, thought maybe his Mama was right. Brownie, his Teddy Bear, fell in the outhouse in 1932. But his Mama pulled him out.

Winds of depression, sickness and heartache may blow across the parched land and we may think that nothing good can come of it. Sometimes you just have to wait…